Conference 19 Blog: People-centred design

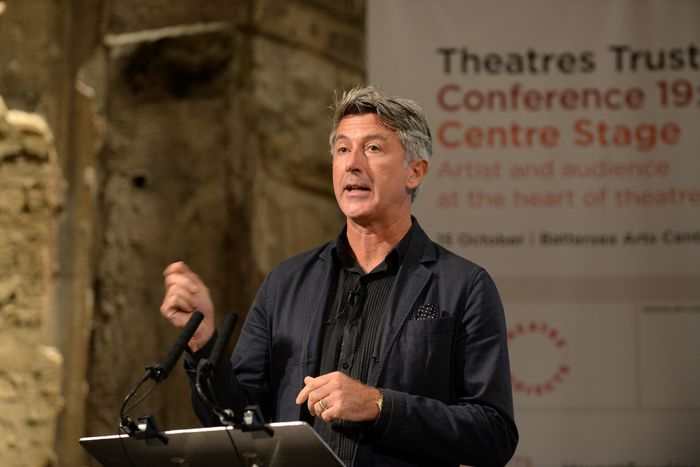

David Micklem's presentation from Conference 19 exploring ideas of cultural democracy and active citizenship.

(View a pdf of the slides that accompanied this presentation here)

I’m going to make just two points. Apologies if I labour them. But I want to make sure I’m as clear as possible.

The first is about Cultural Democracy.

What is Cultural Democracy? At its simplest it describes a simple proposition – that art and culture is unbounded, and encapsulates all kinds of activities – from the personal to the collective, from grime to opera, knitting to line dancing, the West End to fringe to gardening, cooking and everything in between. Cultural democracy underpins a culture that is debated, designed, made…by, with and for - everyone.

What it’s not is the democratisation of culture. The democratisation of culture is the attempt that has been made by arts and cultural institutions to open up to the broadest range of audiences and participants. It’s when a museum curator puts on a major exhibition and his or her colleagues do everything they can to welcome people from all walks of life into their buildings. Or when a theatre or an opera house discounts its tickets to encourage people who might not normally attend to come.

The democratisation of culture has seen brilliant work in outreach, and learning and engagement. It’s developed new ways of communicating with visitors, new marketing strategies and initiatives, fresh thinking around audience development. It’s changed the way some buildings look, opening up civic spaces to people who might have traditionally felt that arts and culture is not for them. There’s been some great work in this space and audiences and visitors have diversified over the past 20 years or so.

But despite this work the Warwick Commission on the Future of Cultural Value in 2016 reported that:

‘in publicly funded formal culture ‘the two most highly culturally engaged groups account for only 15% of the general population and tend to be of higher socio-economic status’.

So that’s the democratisation of culture. I’m talking about cultural democracy. And in doing so I’m laying down challenges. About what is culture? Who gets to decide? How it’s debated? And crucially in the context of today, what role do ordinary citizens have in helping design our arts and cultural spaces – I mean that both in terms of literal space and what gets done within them.

Cultural Democracy isn’t anti professional - whether that professional be an artist or a producer or an architect. Great artists, curators, directors, producers, architects, help us look at the world differently, and make sense of our place within it. But it does challenge the idea that art is only what artists do. It’s rooted in the idea that we are culture – that everyone of the 64 million of us can be actively engaged in its production and presentation, and all the thinking and feeling that surrounds it.

That’s my first point. That cultural democracy is crucial within the context of everything our theatres do. This is a call to arms – I want to say to our arts leaders that cultural democracy is only possible when we relinquish some of the power we’ve worked so hard to attain. Cultural Democracy is where all the citizens we exist to serve get a say in what happens in our buildings – not just the privileged few.

I also strongly believe that the risk of ignoring this – in holding on to all the decision-making power - makes formally defined arts and culture increasingly irrelevant in a society where everyone wants to be actively involved in everything.

Which leads me on to my second point: about active citizenship.

120 years ago, when this building, Battersea Arts Centre, was built we thought of ourselves as subjects. Subjects of the queen.

The principle mass media was the newspaper. It told us the news. It was one way.

We had limited choice – there were only a small range of newspapers we might buy – and we took what we read as fact.

We were subjects.

50 years ago, this building was decommissioned as a town hall and was yet to repurposed as the thriving arts centre it is today.

It was the late sixties, the era of the baby boomer, and we thought of ourselves as consumers. We had choices in our lives and we liked to buy things. We consumed.

Television was the dominant media. It brought the news and entertainment straight into our living rooms. It was increasingly multi-channel and some of it was commercial. It told us things and sold us things.

We had evolved in society – from subjects to consumers. From the Queen to capitalism. From newspaper to TV.

So – if 120 years ago we thought of ourselves as subjects, and 50 years ago as consumers, I’d argue today we see ourselves as citizens.

The internet is everywhere, in our pockets and at work and in our homes. Our dominant media is social, online, connecting us beyond national boundaries around the world. It is limitless and multi-directional. We passively participate and we actively engage. We create content, we debate, we connect.

In 2019 we are active citizens. We want to be involved in everything. We curate our lives. We share with others all over the world. We beta test software (a kind of scratch for the digital age), we create, we comment, we contribute.

But – and it’s a big but – I think that too many of our theatres still treat us like subjects, or maybe consumers. They tell us things and sell us things. They’re usually defined by a privileged few – who set the agenda, define the programme, who hold onto the reins of power. It is these few who largely decide what our buildings look like, and what should fill them.

Very few have adopted the democratising principles of the world wide web. We often visit a theatre to experience one person’s vision for what theatre can be. Too rarely is theatre democratic – decided on by the many, not the few. Not for you, not for me, but for us.

There are increasing opportunities to actively engage in the work on stage but few ways to contribute to decisions about what it is we see. Culture is too often done to us, not with us.

And if we, the people, don’t get to decide what is culture, then why really should we care about it? If I don’t see myself on stage, or stories that speak to me, why should I bother coming, however cheap the tickets are?

So this is my second point. How do our theatres adopt the principles of cultural democracy to change the way they look and what happens inside them?

How do we get our theatres to be more open, more democratic, in everything they do? How do we encourage active participation, active citizenship, in our arts spaces? How do theatres centrally involve ordinary citizens in decision-making, about what and how theatre is made, and how the theatre, the very design of the building, is conceived?

Imagine for a moment, a people’s palace. What might that feel like, when you walk through its doors. A theatre that is designed and programmed, by the people, with the people, for the people.

I said I had two points. But I’ve still got a little time so I want to make a third.

I’ve been talking about people-centred design, about cultural democracy, in the arts for a long time. In this building and buildings around the country and around the world.

The most common response after “that sounds great, how do we do it” is “but doesn’t cultural democracy mean dumbing down?”

“Isn’t there a risk that if you give people power over our theatres we end up with bad design, poor programmes, just entertainment?”

At this stage people often bring up Boaty McBoatface.

“If you ask people to get involved, you get a crap answer. Or the wrong answer. Or a joke.”

And of course I have to mention the B word.

If you ask a question like should we leave or remain in the EU, you get an answer that many of us think is wrong.

My argument is that it’s the question that’s wrong, or a bit crap. And that if you ask question like ‘what should we call this boat?’, or ‘should we leave or remain in the EU?’, you get an appropriate answer.

Ask a better question and I think you get a better answer. And this is where artists and creativity come in. Artists, people who have unlocked their creativity, ask far better questions of us than the two I’ve just mentioned. They are brilliant at getting the very best out of others, at facilitating discussion and debate, in framing a narrative, in imagining a better future.

That’s democracy. Better questions to bring out more informed and creative answers. Creativity at the heart of the debate. Everyone working together, to generate new ideas and to problems solve.

So let’s ask great questions. Of our neighbours and audiences, of our stakeholders and others. Let’s use our expertise, not to dominate the theatres we run, but to create the space in which other people’s ideas can flourish.

Together we can work on a creative revolution. All 64 million of us.

Thank you.

David Micklem, Co-founder, 64 Million Artists

Back to